ABHMS delegation confronts history: Exploring the legacy of Native American boarding schools at Carlisle

Cells where students at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School were disciplined.

VALLEY FORGE, PA (04/30/2024)—On April 8, a delegation composed of Native American pastors and activists, the board of directors of American Baptist Home Mission Societies (ABHMS) and select ABHMS staff visited the site of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. The visit was part of a broader ABHMS inquiry into possible American Baptist involvement in the running of so-called “boarding schools” for Native American children.

Such institutions proliferated between the American Civil War and World War II, with the United States government and a variety of Christian denominations having established hundreds of them during that period. However, the Carlisle School, founded in 1879 by U.S. Army officer Richard Henry Pratt, was the federal government’s first non-reservation boarding school for Indigenous children. Over the next 39 years, thousands of displaced Native American youth who passed through its doors were subjected to the compulsory Americanization that Pratt championed.

The boarding schools were mechanisms for assimilating Native American children and youth into mainstream American culture and Christianity. The government, in concert with Christian denominations, implemented policies that directed the removal of these young people from their families and tribes to mold them into what was then white America’s vision of “civilized people” through a process of isolation and immersion. The schools stripped their students of their Native languages, dress, networks and culture, often in brutal ways. Beatings, starvation and other abuse were commonplace for “infractions” that included students’ speaking their Native tongues. The result of the forced separation and savage treatment: untold hereditary trauma in Native American communities.

The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, a nonprofit dedicated to healing Native American communities affected by boarding schools, states on its website that the U.S. boarding school policy was “expressly intended to implement cultural genocide through the removal and reprogramming of American Indian and Alaska Native children to accomplish the systematic destruction of Native cultures and communities. The stated purpose of this policy was to ‘Kill the Indian, Save the Man.’”

While on their visit, the delegation received historical information from Sandra Cianciulli of the Lakota Nation, president emeritus of The Carlisle Indian School Project, a nonprofit that honors the legacy of the school’s students. Cianciulli described how the school was built with student labor at an inactive military barracks, part of which is now the Hessian Guardhouse Museum. The information about the school currently on display there describes an entirely benevolent educational institution and is silent about the trauma the students experienced. However, Cianciulli pointed to four cells at one end of the building, where children were confined as punishment.

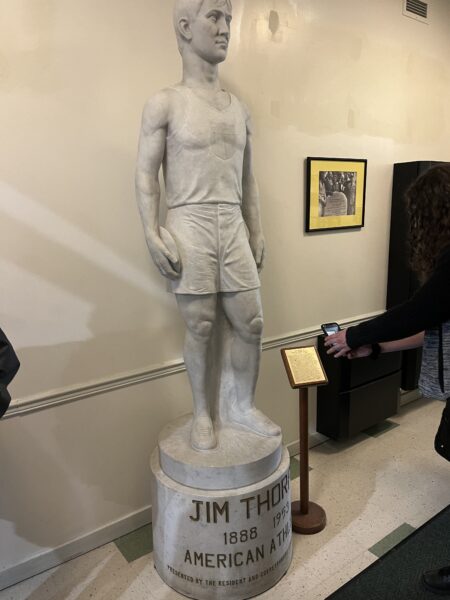

Statue of Jim Thorpe in Thorpe Hall at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

The next stop on the site visit was Thorpe Hall, named after storied athlete Jim Thorpe, a member of the Sac and Fox Nation and called Wa-Tho-Huk, or “Bright Path,” in the language of his people. Thorpe was a decorated football player and a gold medalist in the decathlon and pentathlon events at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden. The statue of Thorpe at the hall identifies him as an “all-American” athlete but fails to mention his Native American heritage.

From Thorpe Hall, the delegation was taken to a cemetery, where rows of white tombstones solemnly mark the graves of 186 children who died during their time at the Carlisle School. In a moving ceremony, Archie Mason of the Osage Nation led a prayer for the children, and Don Robinson of the Tuscarora Nation sang a mourning song, “The Beautiful Place,” in the Tuscarora language. Dr. Janine Pease, a Crow Nation scholar and activist; Quinton Romannose of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations and an ABHMS board member; and Brenda Paddlety Sullivan of the Kiowa Nation, president of the American Baptist Churches USA Indian Caucus, also delivered brief speeches.

An ABHMS delegation convenes at the student cemetery of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Delegation members departed the school grounds for their final stop, the Center for the Futures of Native Peoples at Dickinson College in Carlisle, where Pease gave a research presentation about the Carlisle School’s historical records. Noting that contemporaneous first-person accounts of the 19th century boarding school experience are scarce, Pease read one from a school employee named Zitkala Sa, who had been a student at another Native American boarding school. Sa wrote upon her arrival at Carlisle: “Though my spirit tore itself in struggling for its lost freedom, all was useless.”

Pease went on to identify scholarly work about Native American boarding schools of likely interest to members of the delegation. Among these were “Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, and Reclamations,” by Jacqueline Fear-Segal and Susan D. Rose; and “Education for Extinction: American Indian and the Boarding School Experience, 1875-1928,” by David Wallace Adams.

Protestant denominations were involved in running 72 boarding schools for Native Americans. Presbyterian Churches (USA) and the United Methodist Church have apologized and repented for their actions. However, others with a history of involvement remain silent.

According to Pease’s research, American Baptists were not involved in running off-reservation boarding schools, only “on-reservation” day schools established at the request of the Native American nations. The ABHMS Board of Directors intends to continue its inquiry.

On April 9, Jim Gerencser, associate dean for Archives & Special Collections at Dickinson College, spoke to a packed room at ABHMS’ national event, the Space for Grace & Spiritual Caregivers Conference in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. He imparted a brief history of the Carlisle School and its role in the larger Native American boarding school crusade and went on to describe the work of the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center as a chronicler of the school’s history.

Gerencser has described the Carlisle School, an institutions whose notorious practices were emulated to the lasting detriment of Native American, as “by far the most well-known of the boarding schools.” However, he points out that its considerable reputation was bolstered by “the active propaganda efforts of its founder, Richard Henry Pratt,” and “the success of the school’s athletic teams after Pratt left.”